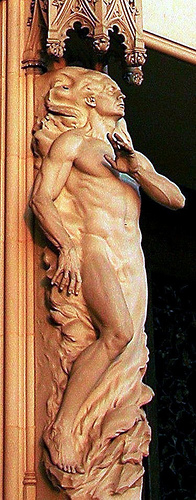

Frederick Hart's "Adam" at the National Cathedral

Why should a dissertation on beauty be addressed specifically to conservatives? Does the topic of beauty hold more relevance for conservatives than, say, liberals? If the answer is yes, as I propose it does, why hasn’t there been more attention paid to the subject of beauty by Republican and conservative leaders? This blind spot about cultural issues has hurt conservative credibility with the public. But, more importantly, it hurts true conservatism at its moral, spiritual and philosophical core. At this critical post 9/11 time of world terrorism, this nation finds itself culturally disarmed, its moral strength sapped. This reason for this decline is no mystery. Conservatives abandoned the culture some time around the end of the First World War. By century’s end much of the old master legacy was being ignored, and major art museums were aggressively collecting postmodern minimalist and neo-Dada works. Beautiful architectural treasures such as Pennsylvania Station were torn down to make room for highways and high-rise glass boxes that destroyed the soul of inner cities in New York, Chicago and Philadelphia. If one political party stands more responsible for the precipitous decline in cultural standards, the other blindly ignored it.

Conservatives clamor to lead in the twenty-first century, but they choose to ignore the legacy of 2,500 years of Western civilization, which could elevate their cause to a higher level. The cultural direction isn’t to the left or right, it’s hierarchical. Beauty provides the key to a door that conservatives have been trying in vain to unlock for almost a century. That door leads to a world that reflects the timeless values and permanent truths that conservatives hold dear: faith, transcendence, virtue, freedom, God, patriotism, natural law, conservation. In short, what I am suggesting is that beauty provides the epistemological structure of a good society—not only through the ideological infrastructure, its laws, religion, customs and government, but in the physical structure of its architecture, homes, public works, monuments, roads and bridges. Most importantly, beauty resides in works of religion, in offerings to God. This is not a new idea. Indeed, it is a very old idea, older than ancient Greece and Egypt, going back to the first evidence of civilization, the cave paintings of Paleolithic man, when art and the spiritual were one. …

In 1990, the then-senior art critic of The New York Times, Michael Brenson, in a full-page editorial titled “Is ‘Quality’ an Idea Whose Time Has Gone?” wrote: “The quality issue works overwhelmingly to the detriment of artists who are not heterosexual, male and white.” Brenson summed up the ideological agenda of a cultural consortium who believed that high culture, particularly Western culture, is oppressive, hierarchical, racist, homophobic and misogynist, oppressing women, non-whites, homosexuals and the poor. Although there is some historical justification for these views, the resolution to dumb down the arts and humanities, to remove standards of excellence, and eliminate the classics and old masters from the curricula of universities and secondary education has lowered cultural standards for the entire nation. When another art critic for the Times subsequently denounced an exhibition of Athenian sculpture from the golden age of Pericles, at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, as “empirical, racist, xenophobic and misogynist,” it effectively ended the long tradition of serious art criticism at The New York Times. The primary function of an art critic is to analyze the success or failure of the artist within the context of a given work of art. The Times was now saying that aesthetics is irrelevant compared to “important” social issues such as poverty, gay rights, gender and racism. The Times position on the arts—all the arts—henceforth would be based on politics. Conservatives wasted the next twenty years protesting the blasphemy and pornography in the art world. What they should have been doing is helping create an alternative. …

No nation in history as powerful as ours, engaged in a clash of civilizations, has been left so culturally defenseless to its enemies. When the Marxist Antonio Gramsci wrote that the soft underbelly of Western civilization lies in its culture, not even he could envision the damage our intellectual class could inflict upon the soul of our nation. Conservatives, who roused themselves to a fury in protest over a few ill-advised fundings in the arts made by a tiny government agency with a budget less than it costs to build one stealth aircraft, missed the entire point. What they should have been concerned about were not the so-called objectionable grants, but what was not funded. …

It has taken forty years of wandering in a cultural desert for conservatives to realize that their leadership, economic and military victories will not supply what is sorely missing from American society. Things continue to get worse. Cultural values and standards continue to decline. Public architecture, monuments and memorials are a national joke. Education has become a matter of class warfare, with children of the poor and middle class shunted into prison-like warehouses. Ultimately, it doesn’t matter who controls the White House, the Congress, state and local governments, or even the Supreme Court. The lens through which most Americans view the world has been ground by the liberals. We see the world as defined by a cultural elite increasingly out of touch with reality. By “lens” I mean the culture: the arts, media, education, history, architecture, literature, music, popular culture, television, movies, fashion and, most importantly, the epistemology of language. Many conservatives revere Ronald Reagan. They should study his Farewell Address to the Nation, in which he warned that “the diminution of cultural values, the loss of civic ritual, will result, ultimately, in an erosion of the American spirit.”